Answering the Call: Our NHS Commonwealth Nurses, highlights the history of the important work done by people from the Commonwealth in the newly formed NHS.

Glenside Hospital Museum in Bristol uses individual histories provided by courageous nurses who travelled from Commonwealth countries to work in the newly formed NHS.

A team consisting of ex-nurses, students and community members documented the experiences of these nurses and then participate in using stitch, print and sculpture to create a display of work that gives an insight into their contribution to psychiatric hospital care. ‘Answering the Call’ has brought the local Bristol community together to reflect and co-create this project, with all participants contributing their ideas funded by Historic England's ‘Everyday Heritage Grants: Celebrating Working Class History.'

Over its 76 year history, the National Health Service has become the largest employer in Britain and one of the country's most diverse workplaces.

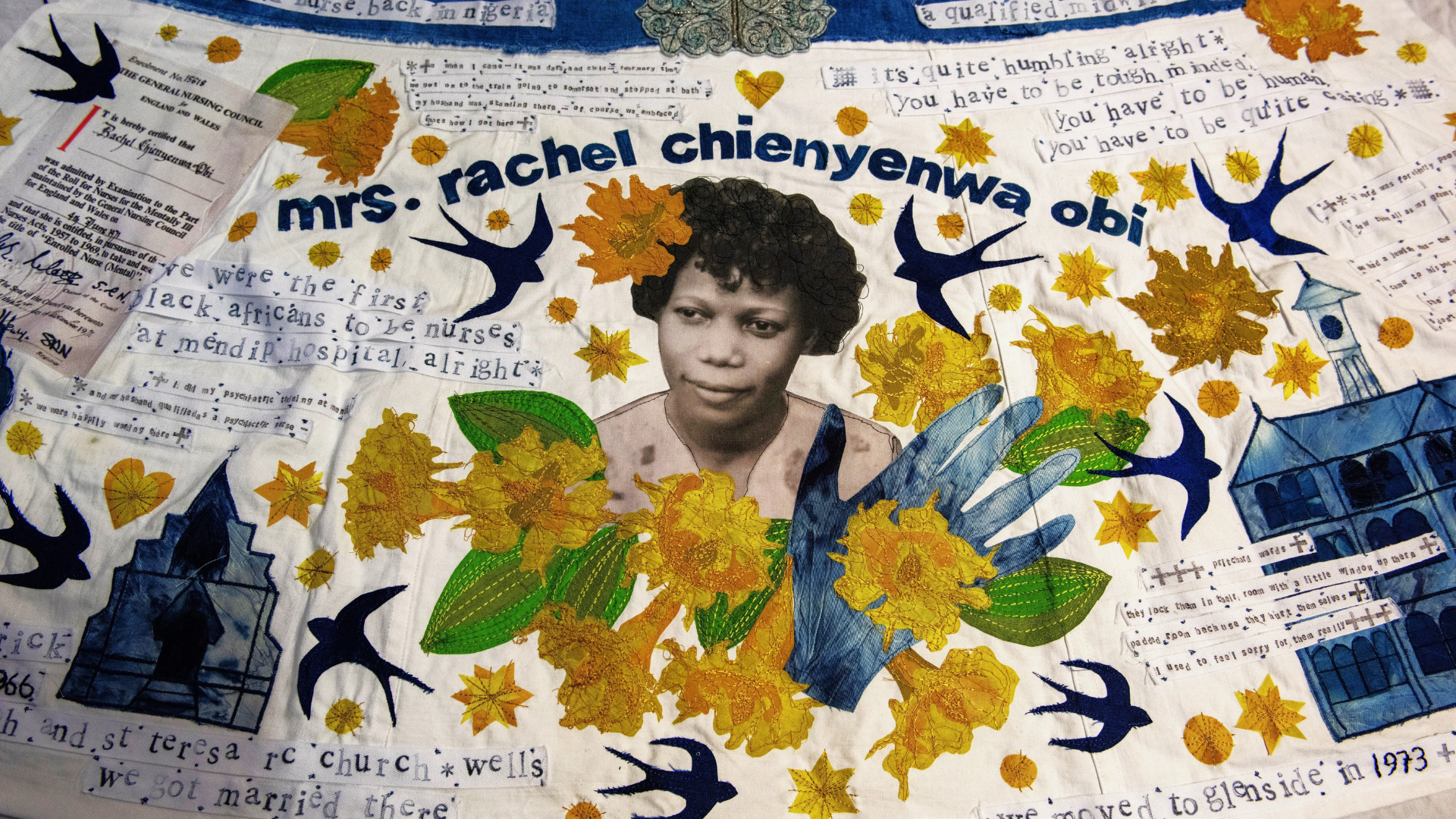

Image: Rachel Obi apron at Glenside Hospital Museum

When the Labour Government of the day took control of 2,688 hospitals on 5 July 1948, there was already a shortage of staff. The 54,000 vacancies were compounded by post-war losses, low wages, and other barriers such as the marriage bar for women. The answer to this shortfall was to call on people to come to Britain. Health Minister Aneurin Bevin (1945-1951), the chief architect of the NHS, planned to recruit nurses and student nurses from both Europe and the Commonwealth.

Antonette Clarke-Akalanne remembers Enoch Powell (Minister of Health 1960-1963), coming to her school in Barbados to encourage female students to become nurses in England. ‘It was an opportunity to get away from my mum, I’d be able to dance and get away from the restrictions of home. So I was excited for me. I did apply and started my training in England in 1960.’ ‘It’s been really important participating in the museum as it contributes to education, as many people will not have known the history.’

Image: Antonette & Irish nurses attending a meeting with the priest while training in Derby, 1960-1964

Enoch Powell’s perspective was that immigrant nurses and doctors should be temporary workers, training in the UK to return to their native countries, which he spelt out in his 1968 inflammatory “rivers of blood” speech, calling got the repatriation of immigrants which split the nation. The day after his speech he was cast out of the Conservative shadow cabinet.

Archival documentation from the time indicates that trainee nurses from Europe struggled to have sufficient English to pass the exams but this was not the case for people from the Commonwealth. An analysis of the 320 trainee nurses at Glenside Hospital from 1956 to 1966 shows 22% were from the Commonwealth, with 17% from the Caribbean islands. At that time, the ethnic minority population of the UK was 1.6%. (1958-1968 training school at Glenside Hospital pie charts: diversity and outcomes)

The Glenside Hospital site has had a nurse training school on-site since 1880, which continues today delivered by the University of the West of England.

In talking with the nurses who trained in psychiatric care it is clear that it involved different skills to that provided by General Nurse training which is very much about physical care. Ex-psychiatric nurse and Environmental Health specialist Jo Forbes-Cooper explains, ‘You have the physical side of the human, the emotional health side and you have the environment you live in and they all intertwine. And if any of them are out of sync it will make the person ill physically or mentally. Susan Kay Pearse (RNM 1968), explained, ‘I learned to put myself in someone else’s shoes and to stop and pause, let someone else do the talking, then really listen. That training has stayed with me. I’m still helping people with anxiety.’

In the Bristol Evening Post, November 1961, John Coe in an article about Commonwealth nurses in Bristol’s hospitals writes ‘We have seen in recent articles that for various reasons coloured immigrants, however high their skill are not employed as crews on Bristol buses’, he concluded that ‘While there is NO coloured prejudice in hospitals there is room for considerable improvement from people outside.’ Celestine Lewis (Nursing Auxiliary 1962-1993) from Jamica was warned that England ‘was not a bed of roses’ and she did recall some patients were not always kind, ‘some of them, you’re looking after them, they said ‘take your black hands off me’’. She was very understanding as she explained, ‘some nurse don't take it. They get upset up. Me say, well she don’t know what she saying, she don’t know what, you know.’

The Victorian hospital, Bristol Lunatic Asylum, understood the therapeutic effects associated with occupation; many female patients were engaged in sewing as treatment. This inspired the project to invite people to replicate this activity through stitching their reflections on the histories of the nurses collected. As one participant explained, ‘the curator told us stories about the activities the nurses provided to distract them from their particular mental plight, I sewed words associated with mental health that I have personal experience with – myself and others in my immediate family’. Another said ‘I sew to repair myself, to help myself stay together.'

Artwork developed to entice visitors to explore this history is on display throughout the Museum in a special exhibition ‘Answering the Call: Our Commonwealth Nurses’ from 17 April – 14 December 2024.

Related

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.